Activities

Small & mighty

Author: Suzie Samut Tagliaferro, August 2022

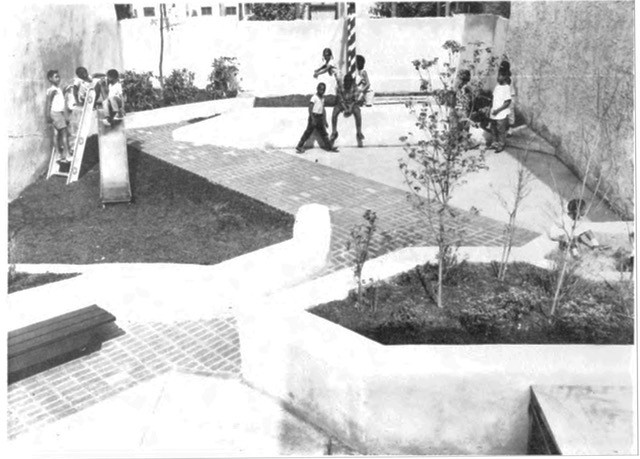

In today’s world, where bigger is better, what happens to green space when our urban surfaces have smaller footprints? Born to Europe in the aftermath of WW2, small neighbourhood parks were constructed to re-invigorate society and their immediate local spaces. Brought to the US in the 50’s, the effort to revitalise local communities was translated by transforming vacant or abandoned lots into playful, usable urban spaces.

Despite the lack of resources during that time, municipalities used their limited available materials to construct local urban parks leading to the creation of the pocket park, otherwise known as a parkette, mini park, or tot lot, tiny playscapes for children. Ref 1: American Planning Association Philadelphia Vest park, Ref 2: Adopt your city The park “Perivolaki Ethnikis Antistasis”

Over the decades, the concept of pocket parks grew increasingly popular, becoming interactive and stylish in their design, where amidst the city’s layer of chaos and concrete, pedestrians have the chance to stumble upon a charming in-between urban living room, spaces perfect to socialise, play or relax in.

During the 60s, a desperate plea for more green space was being demanded by residents in low-income areas. While Pocket parks contribute to a variety of aesthetic and functional benefits, their function as public space lends a sense of ownership to the locals in these areas.

The opportunity to rejuvenate vacant space has the potential to improve the urban fabric of an area, tenfold. No matter their size or shape, pocket parks are tiny injections that effectively improve the well-being of our urban and social environment. Ref 3: Adopt your city programme The park “Perivolaki Ethnikis Antistasis” Ref 4: Charles and Mollison Street Pocket park, Yarra Australia

Together with offering a space for recreation and greenery, the immediate function of a pocket park is to act as a space where people from all walks of life who live in the same community, can peacefully co-exist in a nearby outdoor environment, whilst also having a chance to be involved in the concept, design, and execution of the mini creations.

Areas with heavy congestion and endless asphalt have been softened by space that encouraged sports and play, created a sense of relaxation, offered comfortable seating, and even community-grown vegetable beds. Effectively, these vital urban components that collectively make up a park coated the drabness and deficit of greenery in cities, creating a more positive urban balance. Ref 5: Paley Park Midtown NYC

In most recent times, claiming unused space for creating potential pocket parks is often the case of the councils or community applying for funding or donations by stakeholders. The driving force that boosts the formation of pocket parks is to be fully maintained by community-led foundations or sponsored by an organisation to see the project through. A successful revamped space is one that is studied, analysed, and later designed according to the preferences of the nearby community, also known as data-driven design.

As an example, Newcastle University architecture students held workshops with residents of the area in order to better understand how to improve the main street, Fenham Hall Drive. Conducting qualitative research helped stimulate the residents and urged them to envision the improvement of the main road, leading stakeholders and the community to apply for government funding for the Fenham Hall Drive pocket park. Ref 6: Fenham Hall Drive, Newcastle Pocket Park opening by Newcastle University

Pocket Parks in Malta’s urban environment

By adopting the concept of pocket parks on the island, what we experience as fragmented built-up areas has the potential to be pieced together by useable ‘in-between’ space that could socially and aesthetically bind the country’s urban fabric together.

Revolutionising the use of abandoned lots into functional open spaces holds a responsibility that could greatly encourage social integration in our communities. Plagued with being a car-dominant and poorly planned island, Malta’s pedestrian connectivity has become secondary. Although the over-development is irreversible, our urban fabric has the power and ability to offer pockets of green area that will help relieve the high volume of hard edges that surround us.

To conclude, pocket parks inspire people to walk, rather than drive, which directly forms a bond with the user’s immediate urban surroundings. A much-needed shift to rethink the island’s small open spaces may present a sense of obligation and newfound responsibility for civilians. Moreover, the improvement of the country’s overall physical and psychological well-being may be the most beneficial aspect of these interventions.

Image Sources:

Ref 1: https://www.planning.org/pas/reports/report229/

Ref 2: https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/playgrounds

Ref 3: https://adoptathens.gr/en/thematic-area/prasino-parka-tsepis/

Ref 4: http://www.plannedconstructions.com.au/projects/charles-and-mollison-pocket-park/

Ref 5: https://land8.com/7-top-pocket-parks-small-spaces-with-a-huge-impact/

Ref 6: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/press/articles/archive/2017/11/pocketpark/