Activities

The value of space in urban environments

Author: Thérèse Bajada, August 2022

This short opinion piece is about the value of space. It is worth noting that the word value here does not specifically refer to the monetary value but to the social and environmental value. As a person who lectures in sustainability I consider these two aspects as equally important to the monetary aspect. In fact, the three aspects: social, environmental and financial form the three pillars of sustainable development. On looking at these three pillars from a sustainable perspective, each pillar depends on the other one. It is when the social and environmental aspects are rightly met that the monetary aspect starts to make sense as well – not vice versa.

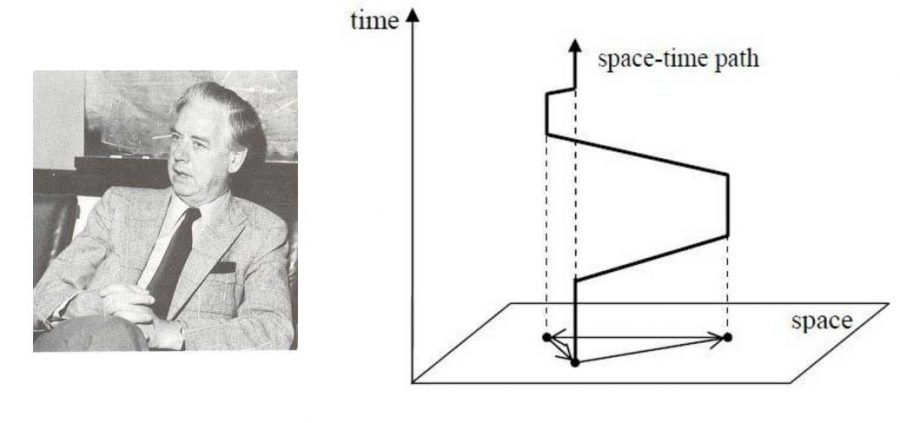

I am a geographer, and as such I am trained to be aware of the space around me. In human geography space refers to the environment that surrounds us, it could be the man-made as well as the natural environment. It further refers to the interactions that human beings have in that environment. Throughout the years several geographers have studied space. For example, the Swedish geographer Torsten Hägerstrand (1916-2004) worked on space in relation to time. He produced the time-space prism (Figure 1) to understand the interactions that individuals have on a daily basis in the environments in which they live and work. As indicated in Figure 1 Hägerstrand posits that individuals have a potential path area that is usually constrained by distance they also travel at particular times with specific velocities, depending on the modes of transport that they use. Figure 1: Torsten Hägerstrand, Time-Space Prism

This prism encompasses also the number of activities individuals are able to do within the space and the time available. These are activities that we all do if we commute or if we carry out leisure activities. We need to travel within set timeframes so we are accessing our destinations and carrying out the activities in space. For this reason, space is an essential element in the environment in which we live. Consequently, opportunities available for the individual while using this space in the set time influence the accessibility of the individual to activities. So, the space available needs to be smartly designed to meet the physical and mental capabilities of individuals. Another important element to consider in this case is the mobility of the individual. The space available needs to cater for primarily vulnerable and active mobility users of the road network – pedestrians and cyclists, followed by public transport users and then car users. This is the sustainable way of using road space – giving top priority to active and vulnerable mobility and least priority to single use vehicles. The plus side to this is an improved environment and better social setting; eventually the economic perspective will benefit because of increased footfall and more interactions with the local activities.

From a planning perspective, Todd Litman (founder and executive director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Canada) refers to space as what goes in between the buildings. The empty spaces are there to be used – wisely. Spaces in urban areas do not necessarily need to be used for buildings or parking spaces. Open spaces, especially if they provide shelter with trees and soft furnishings that include dedicated areas for people to sit and interact provide opportunities for community interaction. Such interaction allows for urban societal issues, such as loneliness and anxiety to diminish. Furthermore, having an open space with trees and landscaping allows for cooler areas in the summer months, aesthetically pleasing environments and the local ecosystems to thrive. The gain that such spaces provide to communities and the environment is worth investing in. Figure 2: Greenwich Park, London, England.

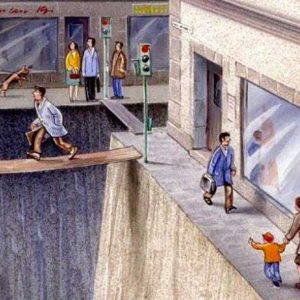

So, what is the value of space? Why should urban environments have enough space that is dedicated to everyone? Currently, space in urban environments, especially in car-oriented societies like Malta, is channeled into investing for the car and road infrastructure. The Swedish artist Karl Jilg depicts the sad situation of roads in urban environments, most of the space is dedicated to the car with very little space dedicated to active travelers (pedestrians and cyclists) (Figures 3 to 5). Figure 3: Limited road space dedicated to people.

As can be seen very little space remains for the communities and for people to walk around and possibly cycle. By attributing the right spaces for commuting, using active travel and having enough open spaces for communities to interact, urban environments can provide a healthy place in which to live and work, enticing a holistic sustainable lifestyle. If used well, space in urban environments has huge potential to instill strong physical and mental health. Figure 4: Active travelers in Madrid, Spain, Figure 5: Cyclists and commuters getting off a boat, the Netherlands

Image Sources: Fig 1: Hägerstrand, 1970; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torsten_H%C3%A4gerstrand#/media/File:Torsten_Haegerstrand.jpg, Fig 2: Greenwich Park, London, England (Source: unsplash.com), Fig 3: Limited road space dedicated to people (Source: Karl Jilg, 2021), Fig 4: Active travelers in Madrid, Spain (Source: unsplash.com), Fig 5: Cyclists and commuters getting off a boat, the Netherlands (Source: unsplash.com)